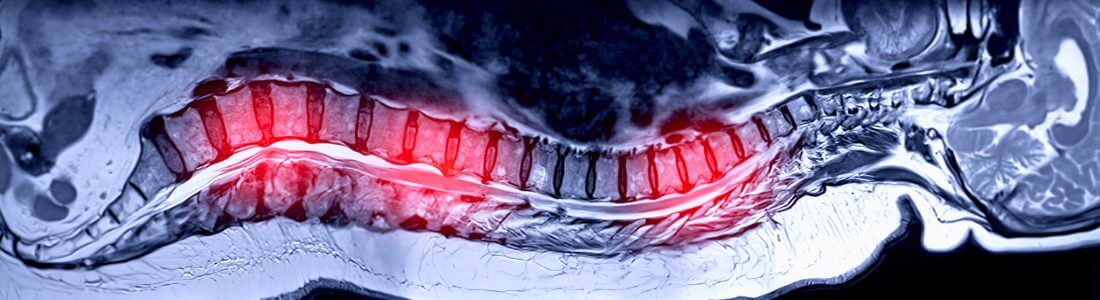

Earlier this week, more than 50 worldwide media organisations revealed the results of a nearly year-long investigation into the safety of over 4,000 medical devices, ranging from artificial hips to pacemakers. The statistics they uncovered make frightening reading: since 2008, the US’s Food and Drug Administration received reports of more than 1.7 million injuries and 83,000 deaths caused by a faulty medical implant. What’s scary for anyone with a spinal cord stimulator is that, of this number, 80,000 injuries and 500 deaths involved an implanted SCS.

Out of all the devices studied, only metal hip replacements and insulin pumps have more injury reports than spinal cord stimulators, but there are far more of those devices in use, meaning that proportionally the SCS has a higher problem rate and one of the worst safety records out there.

What is this report and what’s it about?

This huge investigation has involved reporters from all over the world, working together under the umbrella of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, to focus on the safety of more than 4,000 medical devices that are routinely implanted in patients. Reporters collected and analysed millions of recall notices, safety warnings and medical records, as well as interviewing doctors, patients and whistleblowers.

As well as assessing the safety (or not) of devices, the investigation also aimed to shed light on the somewhat murky procedures around how medical implants are managed; what’s the process for a medical device to get approved in the first place, how do doctors and regulatory bodies ensure that it remains safe, and what’s the procedure when something goes wrong. That work has led to the publication of a website called the International Medical Devices Database. On this website, you can search through more than 70,000 safety alerts and recalls issued for medical devices in 14 countries worldwide.

What does the report say?

The bare statistics are worrying: 80,000 injuries and 500 deaths involving spinal cord stimulators since 2008. Unfortunately, there’s little detail contained in the FDA’s files as to exactly how these injuries and fatalities were sustained. The most common problems seem to revolve around migration of the leads in the spine, unwanted stimulation or discharge, including some people getting shocked, overheating and burning around the battery site, nerve damage and infection. The impact of these problems ranges from muscle weakness to paraplegia to death.

Another big problem is that information is not recorded in the same way from country to country, and some nations won’t release data around so-called ‘adverse effects’ at all. That means it’s very difficult to get a truly global picture of how certain medical implants are working (or not) for people.

The process for approving a new medical device is not sufficient

The other crucial element of the report is looking into how medical devices are approved for use on the public. The BBC has reported that some implants are being used on patients after failing in trials, or after tests that have only been carried out on pigs and dead bodies. It’s important to note that no-one is making this claim about spinal cord stimulators, but nevertheless this is shocking and frightening. As a result, the Royal College of Surgeons in the UK is calling for the establishment of a new register of medical implants, allowing devices to be tracked to monitor efficiency and patient safety over the device’s life term.

I have a spinal cord stimulator or I’m considering getting one. Should I be worried?

I’m absolutely horrified to see the number of people who’ve been injured or even killed by their decision to get a spinal cord stimulator, but the reality is that it’s a high-risk implant and a high-risk surgery. That’s why it’s generally only offered as an option of last resort for people with chronic pain that hasn’t responded to other therapies.

For most people it’s safe and very effective at helping with their pain; manufacturers are keen to point out that more than 60,000 systems are implanted in patients each year and the majority experience no problems and obtain good pain relief of more than 50%. I’ve had my SCS since 2012 and it’s been life-changing; the idea of being without it is terrifying.

However, clinical trials show that up to 38% of people who’ve had a permanent SCS implanted have problems with it. These issues can be related to the hardware itself, with lead migration, breakage or connection failure requiring additional surgery to correct. Infection is another problem; as the leads are being placed into the spine itself, if any bacteria enters at the same time it’s on a direct pathway to the brain and can cause serious complications. Up to 12% of patients also complain of ongoing pain at the site of the implantation, and for other people, unfortunately, the SCS surgery is the trigger that can cause their CRPS to spread.

It’s a controversial treatment amongst chronic pain sufferers; generally people either love it or hate it. I love my SCS, but I know several people who are devastated they ever took the risk of having a stimulator implanted. One friend is now counting the days until the system is surgically removed as it’s become so painful for her.

Do your research and ask questions

The most important thing anyone can do before deciding to go ahead with a spinal cord stimulator is to do as much research as they possibly can:

- Ask every question you can think of to your consultant. Make a list before you go to the appointment so you can ensure you don’t forget anything.

- Read everything you can about the implant and the surgery. There are many articles and blogs on the internet where people have shared their own experiences.

- Ask questions of people who’ve already got the implant. There are friendly Facebook groups for people with spinal cord stimulators who’ll happily try and answer your questions. If you have a condition that’s often treated with an SCS (like CRPS) then try and find groups for your condition so you can ask people with similar medical problems about their experiences.

Likewise, if you already have an implanted SCS and you have concerns, the first port of call is to contact your hospital and ask them for advice.

What difference will this report make?

I hope that the recommendation for a database of medical implants is implemented as that would provide clarity around the real rates of success of these medical devices. A fundamental issue is the simple fact that these implants are made by huge companies with huge profits and so there is always pressure for them to make money, instead of simply following what’s in patients’ best interests.

It’s only if we start to closely follow patients with devices like spinal cord stimulators, using a standardised form of monitoring that’s consistent worldwide with an agreement every country will share data that we will really start to get a true picture of the positive and negative impact they can have on patients. I hope very soon we’ll all have true clarity of how good or bad particular treatments can be.

You may also be interested in the following articles:

Spinal cord stimulation for CRPS: my experience

Spinal Cord Stimulation: Low Frequency vs High Frequency

Are Dorsal Root Ganglion (DRG) Stimulators set to replace Spinal Cord Stimulators (SCS)?