Spinal cord stimulators are, to put it mildly, a controversial topic amongst sufferers of complex regional pain syndrome. In some support groups, asking for advice about an SCS feels a bit like throwing a grenade into the room; duck and cover, wait for the explosion to happen, and then tentatively check if it’s safe to go back in there yet.

Spinal cord stimulators are divisive as people can have very differing results. Some patients find them fantastic and obtain an effective reduction in their daily pain. Others undergo the implant surgery, only to discover that the operation itself causes a spread in their CRPS symptoms, and after all that, the SCS itself provides little effect on their pain. So, what’s the lowdown?

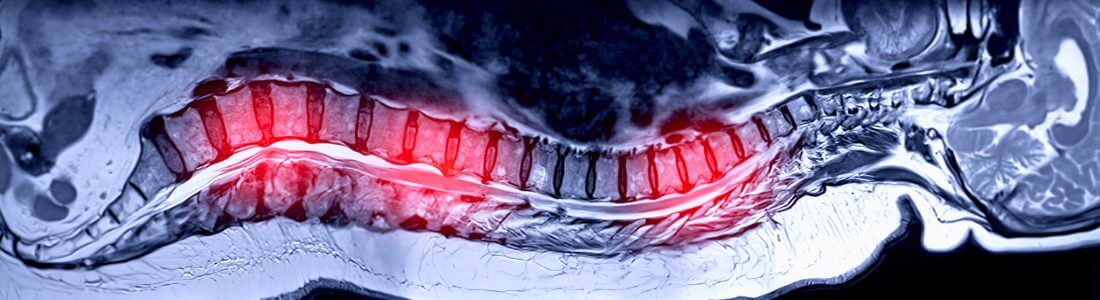

A spinal cord stimulator comprises electrodes in a lead that sit in the epidural space of your spine, coupled with a battery that is placed either in your hip or abdomen. The electrodes are placed at the level in the spine where the nerves from the CRPS-affected area join it. This means that each stimulator is individually sited; for my lower left leg pain, the lead is positioned in the middle of my back, but for those with arm pain, it’s higher up towards the neck.

The idea is that a small electrical current interrupts the pain signals from the nerves, meaning that fewer pain stimuli reach the central nervous system, so less pain is felt. Generally you feel a tingling sensation over the painful area instead. The patient can turn the implant on and off and control the level of the electric signal with a small handheld device.

As specialists, we understand CRPS. Speak today, informally and in complete confidence, to one of our specialist solicitors on 01225 462871 or email us. We are confident you will notice an immediate difference and a very different service from your current solicitors. |

Treatment for CRPS

Spinal cord stimulators have been used for treatment of CRPS since the mid ‘80s, and there is a substantial body of evidence to show that they relieve pain and improve quality of life. I had my SCS implanted in 2012 and then a second electrode lead added in summer 2016. It is by far the most effective treatment I’ve tried for my CRPS and I would definitely make the same decision again. My SCS controls my pain and gives me back my life and I am forever grateful for it.

It sounds good and it undoubtedly can be. However, there are some downsides to this treatment that any patient should be aware of before they go down this road. To be clear, I definitely recommend exploring whether an SCS would be right for you, but I also suggest being aware of everything that goes along with this option.

Firstly, the operation to implant the permanent SCS is a big one. It took me months to get over each operation. Each time, I needed care and help from my family for a number of weeks before I could take care of myself again. The second operation was worse for me as the surgeons were operating again in the same part of my spine, and six months on, I still have some spinal pain.

The next issue is linked to this: it’s hard to stitch the electrodes into the spine as there is simply not much there to stitch it to. This means that the electrodes are largely held in place by scar tissue, which takes a few months to form after the surgery. Even a minuscule movement in the position of the electrodes can completely change how the stimulation works, with the patient either feeling stimulation in the wrong area or not feeling any stimulation at all. Therefore everyone is advised, after their implant operation, to avoid bending or twisting more than a tiny amount for the next three months. It’s really difficult to stick to this. Opening a low drawer, picking something up off the floor, getting in and out of the bath – they all become very tricky when you can’t bend or twist. It’s even harder if you add pets or small children into the mix.

Complications

Despite my extensive caution, at my 3 month follow-up after the first operation I was told that my lead had moved a few millimetres. Luckily my stimulation still worked well, but it could have been disastrous and there is no way I could have been more careful than I was. I know of other people in the same boat. It can make someone feel very guilty, like they’ve been given this chance to control their pain and then wrecked it themselves. It’s not a good way to feel. If your lead does move (or ‘migrate’ as the doctors call it) then the only way to reposition it is through more invasive and painful surgery.

Another unpleasant possibility is that for some sufferers, the surgery itself can cause a spread in their CRPS symptoms. I know people who’ve had CRPS pain develop around their implant sites in their spine and abdomen which is pretty devastating. You’re also going to need more operations to maintain the SCS; the battery will need to be replaced every so often, although thankfully this is a pretty straightforward procedure carried out in day surgery. It’s also sadly shown by research that the efficacy of your SCS will decrease over time. Doctors warn you that if it provides 7/10 relief at first implantation, it will not stay at that level forever. Having said that, five years on, my SCS is still as effective as ever, but that’s only my experience.

Spinal cord stimulation is also an expensive and complex treatment, which not every NHS Trust will fund and not every hospital is experienced in providing. I was lucky to live in London, where I quickly obtained fully funded treatment from a team who perform these operations weekly. However many CRPS sufferers in other parts of the country have to appeal themselves to their NHS Trust for the money to undergo SCS treatment. They’re not always successful. It’s a sad and deeply unfair postcode lottery.

There are also people for whom spinal cord stimulation just doesn’t work. Maybe you can’t stand the tingling sensation, or the doctors can’t get the electrodes positioned right to cover your pain. This is why you will have a trial of the stimulator before the full system is implanted. If your trial is deemed successful by your doctor, you’ll proceed to full implantation. The criteria for success are based around impact on pain score, medication and activity levels. There can be distressing disagreement on what constitutes success: a patient may be desperate to have the full implant but their doctor may say the trial didn’t help them enough to undergo full implantation. That is a terribly bitter pill to take.

Learning to live with SCS

Once installed, you do need to learn to live with your SCS. Going through an airport metal detector becomes a no-no. You probably won’t be able to have an MRI unless your SCS is MRI-friendly. You’ll probably need a medical alert bracelet. Going in and out of some shops might turn the stimulation up or down. The first time you sneeze with it on will be an eye-opener. You might have to work out how to schedule the recharging procedure so you’re not suddenly left with a dead stim. And undoubtedly (it happens to everyone) you’ll have one day where you forget your controller (and then never ever do it again).

An SCS is not a miracle cure. It’s a tool, like crutches or medication, that helps you to live a better life. Sadly it doesn’t work for everyone, but for me, it remains the most successful treatment I’ve had and I would do exactly the same again. I encourage anyone offered an SCS to explore it fully and weigh up all the factors involved for you personally before you decide to trial it or walk away; no-one but you knows how it will work for you. If it’s not right it’s not right, but it might just help you a lot.

Search our extensive archive of articles covering every aspect of living with CRPS. |