In earlier articles we have touched upon the problems that can arise in a personal injury claim involving chronic pain, as a result of the subjectivity of pain.

It is accepted that the experience of pain between individuals can vary significantly. Such individual differences in the experience of pain are, understandably, extremely difficult for an observer to appreciate. However, in numerous scientific studies over many years, huge differences between individuals have been consistently observed.

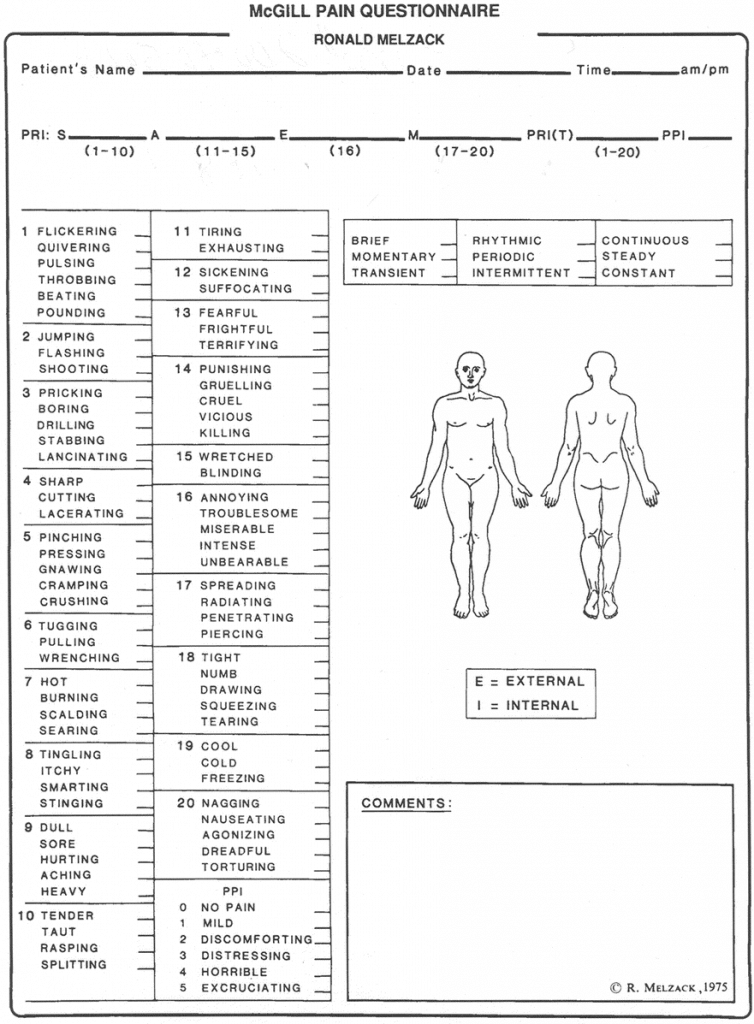

People describe their pain in entirely different ways. The most common way to rate a person’s pain is by reference to the McGill Pain Questionnaire. This was developed in the early 1970’s by two researchers at McGill University in Toronto. By selecting descriptive words from a number of groups, a person can provide a doctor with a good indication of the nature and intensity of the pain they are experiencing:

Some people suffering chronic pain are better able to function than others. That is a fact. This is something that I see regularly among my clients. Some manage to continue working and looking after themselves and their families. Others, who formerly led busy working and home lives, are reduced by their chronic pain state to a near-housebound condition. There are also, of course, many others whose circumstances lie somewhere between these two extremes.

In the context of a personal injury claim, even somebody with objective physical signs of a chronic pain syndrome can expect to have their credibility challenged. Sceptical defendant insurance companies and their legal representatives are understandably wary of reported levels of pain (and therefore disability) that can be measured only by a claimant’s self-reporting.

Reference to the McGill Pain Questionnaire consistently supports the view that Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is the most painful medical condition known. Accordingly, a claimant satisfying the diagnostic criteria for CRPS should have little difficulty persuading a medical expert in their claim that they are suffering debilitating pain. However, a claimant suffering from a more poorly defined chronic pain syndrome and/or chronic pain disorder can be more open to allegations of over-reporting and/or malingering for personal gain.

I have previously discussed that mention of “chronic pain” to an insurance company is inevitably treated like a declaration of war, even for those suffering CRPS. The full panoply of weapons are mobilised, including covert surveillance and the monitoring of social media. But unless such intrusions reveal clear and obvious inconsistencies between reported and observed symptoms, what can they really prove? The answer is, little if anything at all. And that is the key point. If a claimant can maintain their credibility, they should have no difficulty persuading the court of the veracity of their case.

As a solicitor, my role is to help my clients maintain their credibility. That is achieved through forensic preparation, regular communication and the use of clear and concise language in documents.

Forensic preparation

There must be no surprises – get everything into the open at an early stage. At the outset of the claim, the solicitor must obtain and review meticulously all relevant records – medical, employment, DWP, military etc. If there is anything in those records that requires explanation or clarification by the claimant that should be done immediately, most likely in the form of a witness statement from the claimant.

Regular communication

It must be drummed into the claimant that if they have a better day, can walk a little further or can undertake another activity for a little longer, they should inform their solicitor immediately. That enables the solicitor to pass on that information to the defendant’s insurance company or solicitor in context. If the claimant’s better day has been caught on camera, their volunteering of that information expunges any suggestion of deliberate exaggeration.

Clear and concise use of language

Claimants must be encouraged to explain exactly what they mean. This is particularly important in documents such as witness statements and when giving a history to a medical expert or treating provider, who will make a note of what they are told. For example, when the claimant says that they cannot walk further than 50 metres, is that what they really mean? Probing a little further may reveal that it would be more accurate to say that they often find it difficult to walk more than 50 metres before their levels of pain increase significantly. In other words, they can walk further than 50 metres, but not without significantly exacerbating their pain.

If this is explained very clearly in the document, when the surveillance shows the claimant walking 80 or 100 metres, they will not automatically be deemed to have contradicted themselves. In fact, it may be possible to ascertain from the footage that the last few metres are walked with extreme difficulty, thus corroborating their account and further supporting their credibility.

On a final note, since a change in the law in April 2015, the court now has the power to dismiss the whole of the claim of an otherwise perfectly genuine claimant, if it is satisfied that they have consciously exaggerated even a relatively modest aspect of their claim. Consider the walking example above – a sobering thought!