In recent years I have increasingly seen mention of the ‘Biopsychosocial model’ as being the optimum way to both view and treat chronic pain as well as disease more generally. Whilst it might seem easy to dismiss this term as some new psychobabble, it seems that it’s not just the psychiatric profession using it; in the context of chronic pain it’s a term now used regularly by rheumatologists, pain medicine specialists and others operating at the coalface of treatment.

What exactly is the Biopsychosocial Model?

After discussing the idea for this article with colleagues, one very helpfully sent to me a learned paper he’d come across. “This may help” he said. It didn’t. After several pages of mention of Freud, Engel, Grinker, Jaspersian methodology, medical humanism and dogmatism, I headed off in search of a cold compress.

One thing that article did highlight, however, was that the Biopsychosocial (BPS) model, or certainly the principles behind it, are certainly not new. But what exactly is it?

Essentially, the BPS model is a way of looking at the wider causes of disease. Until relatively recently, it had been common to view disease as largely the result of biological factors only and to treat it accordingly; a purely biomedical approach. However, it is now accepted that this is way too simplistic. Chronic medical conditions invariably have multiple, interlinked causes which continually affect (or infect) one another, perpetuating and exacerbating a person’s overall condition.

To achieve the very best outcome for the patient, the BPS model highlights the importance of treating or addressing all causes of the condition, not just one or two in isolation.

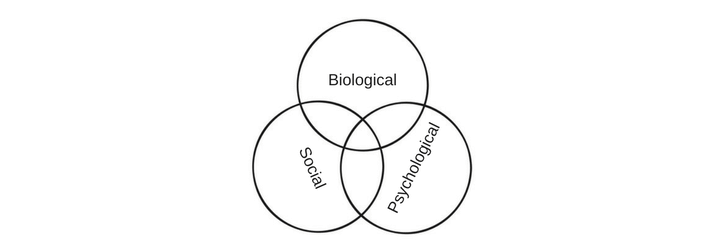

Perhaps the best way to visualise the the model is to think of it as a Venn diagram of three overlapping circles, labelled respectively Biological, Psychological and Social. Biology can affect psychology, which can affect social well-being, which can further affect biology and psychology, and so on.

Let’s take an example

Katy develops Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) in her dominant right arm, severely restricting her function. The biological component of the model takes into consideration (non-exhaustively) factors such as:

- genetic and other pre-dispositions;

- the autoimmune system;

- brain chemistry;

- the effect of medication;

- the fight-flight response;

- her psychological response.

That of course leads us neatly to the psychological component. The biological factors may influence how Katy feels about herself:

- her thoughts;

- her emotions;

- her behaviour.

She may develop low self-esteem, fear for the future, and a fear of the judgement of others, all ultimately leading to anxiety and depression. As a result of these factors, Katy may begin avoiding certain situations, avoiding people, staying at home or leaving her job. As her world and her outlook is compressed, her anxiety and depression worsen.

The social component of the model examines the related social factors influencing Katy’s health; her interaction with other people, her worsening financial situation, her declining overall physical fitness and mental well-being.

Perhaps Katy has a young child and her pain means that basic mother/child physical contact is necessarily limited. It means that she struggles to bathe and dress her child or prepare its food. Her partner steps up to the mark and her mother also offers to help out but maybe Katy perceives underlying resentments. These further stressors may lead to the exacerbation of Katy’s biological and psychological problems which then further exacerbate the social problems, and so on, perpetuating a downward spiral.

Treatment

Once chronic conditions can be visualised in this way and the interconnecting nature of each of the components can be seen more clearly, it becomes easier to understand how the BPS model can form the basis for treatment.

Of course, I have to qualify what I’m about to say by stressing that I’m no expert in either the BPS model or the treatment of chronic pain. However, if Katy’s treatment is limited to the biological component – perhaps her pain medicine specialist adjusts her medication, performs nerve blocks and/or implants a spinal cord stimulator – whether or not that helps in reducing her pain, it is unlikely to have a significant effect upon the psychological or social factors.

But if, in tandem with treating the biological issues, perhaps Katy sees a psychiatrist to consider any requirement for antidepressant medication and a psychologist for therapy, then more of the components of her overall situation are starting to be addressed. And say (very much ignoring the cost!) Katy could be provided with some help around the home and with childcare, thus reducing the additional pressure on her partner and mother. Might that help to address another stressor?

As Katy’s overall outlook improves a little, perhaps she and her partner can start to occasionally venture out again together, initially just to the cinema or for a quick pizza. Although she is still unable to consider a return to her career, perhaps Katy finds a part-time voluntary role advising or helping other people. She starts to feel a little more secure in her relationship and with the voluntary work her sense of self-worth begins to improve. This in turn helps to further improve the psychological and biological factors.

Conclusions

Of course, some may be quick to dismiss all of this as hypothetical nonsense, a counsel of perfection not reflected in the real world. But the point is (and maybe it’s just me), I’m starting now to see how such an all-inclusive approach can significantly improve the prospects of achieving a more positive outcome to treatment than by solely adopting the more traditional (and rather blinkered) biomedical approach.

Having read around the subject for the purpose of writing this article, I have to say that it barely begins to scratch the surface of the BPS model. However, one thing I do understand are my own limits and I’m very content to leave the detail to those far cleverer than I. At the very least though, and much against my initial expectations, I believe that in just some small way I now at least understand the basic principle of the model.

More broadly, the BPS model has been a significant driver behind the development of the most effective interdisciplinary pain management and rehabilitation programmes. It is now widely accepted that for those with established chronic pain, attendance on such a programme vastly improves the prospect of achieving increased function and thereby an improved quality of life.

You may also be interested in the following articles:

Emotional Awareness and Expression Therapy (EAET) for Fibromyalgia

A Beginner’s Guide to Mindfulness for CRPS and Chronic Pain

The good, the bad and the quacks: false hope in the “treatment” of CRPS and Chronic Pain

Hushed up? Could a simple antibiotic successfully treat therapy-resistant CRPS?

Where can I access Residential Rehabilitation for Chronic Pain?